The following links and information from within are resources from the idea development of adding an additional layer to the existing Australian parliament. As a group we decided that a mobile architecture’s benefit is reaching people, and looking at Australia, we have a lot of people spread out across the middle of the continent in rural remote areas, these areas are generally difficult to physically access (and as such are not frequented by politicians) and make it even harder for these people reach parliament to have their voices heard. The aim of creating an architectural response to this is to return the focus to the fact that the backbone of our nation requires more support, our economy relies in part upon decent management of these areas and the people forming this backbone of our nation deserve appropriate and effective representation.

http://www.australia2020.gov.au/topics/docs/rural.pdf

Indigenous Australians, as managers of one-fifth of the land in Australia, could play a major role in rural Australia's future.

A strong and sustainable agricultural sector is the foundation of many of our rural and regional communities.

Tourism offers enormous growth potential as well as diversification benefits.

As Australia is a major commodity exporter, the mining industry will continue to underpin the growth of many of our rural communities.

Climate change creates opportunities as well as challenges for rural and regional areas. Solar, wind and geothermal energy tend to locate in regional areas where large quantities of land are relatively inexpensive.

The provision of biodiversity and carbon abatement are examples of "ecosystem services". They will grow in economic importance to rural and regional Australia in the future.

http://epress.anu.edu.au/anzsog/fra/mobile_devices/ch04s02.html

There is a significant population imbalance in Australia. We are just about the most urbanised country in the world. Approximately 82% of the Australian population lives in major metropolitan regions and within 50 kilometres of the coast.

As the population distribution continues to change, so, naturally, does the level of attention and understanding that governments have of rural issues. It is here that it becomes clear that Australia’s system of government has not adjusted to accommodate these changes.

From the perspective of rural communities and agricultural industries, there are two major reasons why we need to look to reform of our system of government, to overcome and compensate for this institutionalised lack of understanding:

-One is the hidden costs to the entire Australian community of poor decision-making in relation to rural issues.

-The second is the human and social impacts of change affecting rural areas, which are not being effectively addressed by the current system.

http://www.roundtheworldflights.com/rtw-blogs/index.php/news/march/717-the-problem-with-canberra.html

Canberra, it is fair to say, doesn’t have a particularly good reputation. It is seen as a plastic, artificial city which has only one redeeming feature: acting as a holding pen for politicians.

It was built to a plan drawn up by American architect Walter Burley-Griffin, who envisioned a big lake in the middle, created by damming the river. He also came up with grand buildings built around sightlines of each other (in a blatant rip-off of what Washington DC does), plenty of open space and far, far too many roundabouts

It is a city designed for motorists. Motorists who know exactly where they’re going and have no intention of pulling over to check a map or, god forbid, park. Yet seeing a traffic jam in Canberra is something of a rare privilege. This is partly because the design is successful – traffic flow is king here – and partly because of Canberra’s main problem. And that problem is that there’s just too much space.

The city has more suburb names than houses (or so it seems). There’s nothing high rise, and it all just sprawls merrily into seemingly infinite space. Living must be incredibly pleasant – no congestion, no overcrowding, parks and nature reserves at every corner – but it doesn’t half make the city a chore for the visitor.

Canberra’s roads are eerily quiet. The huge pavements never have anyone walking on them. Only the car parks are full. It’s like someone has designed the perfect big city and forgotten to fill it with people. As such, it feels as ridiculous, as lost, as forlorn and hollow as a tiny child clad in clothes that it’ll “grow into”.

To create a fire, you need to rub sticks together. If those sticks are miles apart, it doesn’t work. A city needs a certain element of claustrophobia, it needs frictions, it needs people having to fight to create their own space. Maybe, when they finally fill it, Canberra will have that.

http://www.businessspectator.com.au/bs.nsf/Article/The-costs-of-Canberra-pd20100325-3URWK?OpenDocument

Politicians are asking talented people to make two sacrifices, should they ever want to serve the country,” Neville says. “A financial one and a lifestyle sacrifice. The financial sacrifice can be overcome, but the lifestyle sacrifice is very hard. Either Canberra has to triple in size to a population of about 2 million, or we need to devolve the Canberra bureaucracy out to the capital cities. Another problem with Canberra in its current form is that it is no more than a large company town and so susceptible to the problems of group-think.”

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/roots-of-the-rural-revolt/story-fn59niix-1225913605950

The bush is littered with issues such as globalisation, satellite towns v regional centres v cities, and multinational lobbyists v grassroots movements. This rural revolt also reflects Australia's love of the underdog.

Political scientist and former University of Canberra vice-chancellor Don Aitkin said that, "Australia depends on its primary producers for its high standard of living, for only those who produce a physical good add to the country's wealth".

All the major parties have decided to back a framework which will have very little regard for distance, remoteness, smallness and social equity . . . the very policies that are emanating from this place, whether they be fuel policy or aged care policy -- even policies relating to country doctors or the lack thereof -- are emanating from that basic policy framework, which has not delivered equity to country constituents in particular.

"The message that the policy sends to country communities is to proceed to your nearest major regional centre, go to the coast, go to Sydney or go to buggery."

http://www.usda.gov/wps/portal/usda/ruraltour?navtype=TOUR&navid=TOUR_MISSION

Policy precedent?

-similar scheme?

http://www.dfat.gov.au/facts/regional_australia.html

The healthy, friendly and safe environment and community lifestyle of regional Australia attracts many people from the cities.

In 2006, regional Australia contributed around $65 billion, or about 67 per cent, of the country’s export revenue.

Major sectors of the Australian economy—resources, energy and primary industries—are located in regional Australia.

Regional Australia continues to be the economic backbone of the nation’s prosperity, especially with exports like minerals, grain, wool, beef, seafood and wine.

Regional Australia is home to some of the most geographically isolated and remote communities in the world

http://www.nff.org.au/farm-facts.html

Australian farms and their closely related sectors generate $155 billion-a-year in production - underpinning 12% of GDP.

Australian farmers produce almost 93% of Australia's daily domestic food supply, yet Australia exports a massive 60% (in volume) of total agricultural production.

Australian agriculture has important linkages with other sectors of the economy and, therefore, contributes to these flow-on industries. Agriculture supports the jobs of 1.6 million Australians, in farming and related industries, across our cities and regions – accounting for 17.2% of the national workforce.

Farmers occupy and manage 61% of Australia’s landmass, as such, they are at the frontline in delivering environmental outcomes on behalf of the broader community.

The following maps are our look at the various climatic,social,infrastructural zones etc. of Australia. These may inform how mobile architecture might best be used in regional Australia:

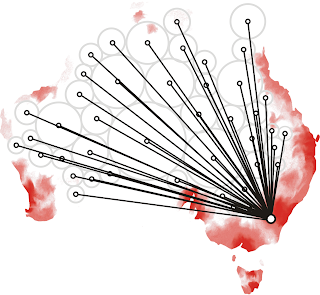

As such we responded by proposing that regional Australia may be subdivided into smaller zones, each allocated a particular mobile architecture to represent them. This would rely on existing and new infrastructure to link the regional zones, and would also have to project into the future some form of estimate to growing areas of population, climate change, available resources etc. Below are some conceptual diagrams whic to begin to show this idea: